Agriculture, Specialty/Niche, Sustainability November 01, 2020

Passion in Paradise

Love of agriculture takes root in Trinidad.

The island of Trinidad glows with color: brightly painted houses, a robin’s-egg sky, and a thousand shades of green in the fields and forests that are crammed with plant life exploding into lush growth. That energy also pervades the island’s young farmers, an almost explosive entrepreneurial spirit.

I was in Trinidad—the easternmost island in the Caribbean, just seven miles off the coast of Venezuela—as an officer of the International Federation of Agricultural Journalists, participating in a workshop for fellow reporters. I stayed a couple of extra days to visit some farms, and left with a deep admiration for the passion driving Trinidad’s young farmers.

Daryl Knutt raises goats, cattle, forage, and a wide range of local fruits and vegetables on 10 acres in southern Trinidad. He’s putting his two master’s degrees in agriculture and sustainability to work as he carves a diversified, integrated operation from what was a thicket of head-high bullgrass. He and his peers are also grappling with world-class bureaucracy, warding off thieves, and struggling to access capital.

“We have a youth base kind of hell-bent on getting things done and not accepting folly,” Knutt says. “Because of that determination, I would think we will make progress on some sort of food security.”

Kizhara Harris enjoys the aroma of roasted cocoa beans at Brasso Seco Chocolate Company.

Life in Trinidad has always required determination.

Back in its days as a Spanish colony, Trinidad was neglected by the conquistadors, overshadowed by the glitter of Peruvian gold and the richer sugar plantations on Cuba and Jamaica. It didn’t fare much better under French planters in the 1780s or the English, who took over in 1797 and amped up the plantations with more slaves from Africa and, after the abolition of slavery in 1833, laborers from India who were largely treated like slaves during their 10-year indentures.

Diverse farms. Today, the 1.4 million residents of Trinidad and Tobago, a two-island republic, are almost evenly split among Black, East Indian, and mixed heritage. Though Trinidad is just 25 miles long and 7.5 miles wide, the island’s farming is almost as diverse as its people, from the spices and cocoa of the northern mountains to the coconuts of the east and the vegetables of the southern mangrove swamp.

Trinidadian food is a blend of Indian curries, African root vegetables collectively called “provision,” Spanish salt cod, and pit barbecue called “buccaneer cooking” after the local pirates who perfected it.

Alicia Charles, founder of Liguaya Agri Business, says the nation’s future—and health—lie in traditional crops. There is great value chain opportunity for healthy, sustainable, indigenous foods and drinks.

“COVID-19 showed the world why we need to eat better, to be healthier, with locally grown foods,” she says.

Trinidad’s cocoa hybrid, Trinitario, is celebrated for its flavor.

From red-bearded hill rice (Oryza glaberrima) taken from Africa to Trinidad with shiploads of slaves centuries ago to papayas to eye-watering Scorpion pepper, Trinidad’s traditional foods offer alternatives to the modern diet that could help today’s residents battle diabetes, hypertension, and cancer, she says.

De-colonizing. Focusing on a local food system would require throwing off centuries of colonial economics. Colonies like Trinidad and Tobago were groomed to export raw materials to their European conquerors and import necessities to keep those same European economies humming.

One colonial commodity that Trinidadians are taking back is cocoa—specifically Trinitario, an 18th century local hybrid renowned for its complex flavors.

Along the road through the northern mountain village of Brasso Seco, Kelly Fitzjames steps into the undergrowth, lured by a cocoa pod nearly a foot long, glowing yellow in the diffused light of a rainy afternoon. It’s a remnant of Brasso Seco’s origins as a cocoa plantation town in the early 1800s, when Trinidad was the world’s third-largest cocoa producer. After the industry crashed in the 1920s in the face of competition from West Africa and Brazil and the nation’s pivot from agriculture to oil, Brasso Seco’s plantations were swallowed by the forest. After the government quit its single-desk buying program in 2011, it seemed the last nail had been pounded into cocoa’s coffin.

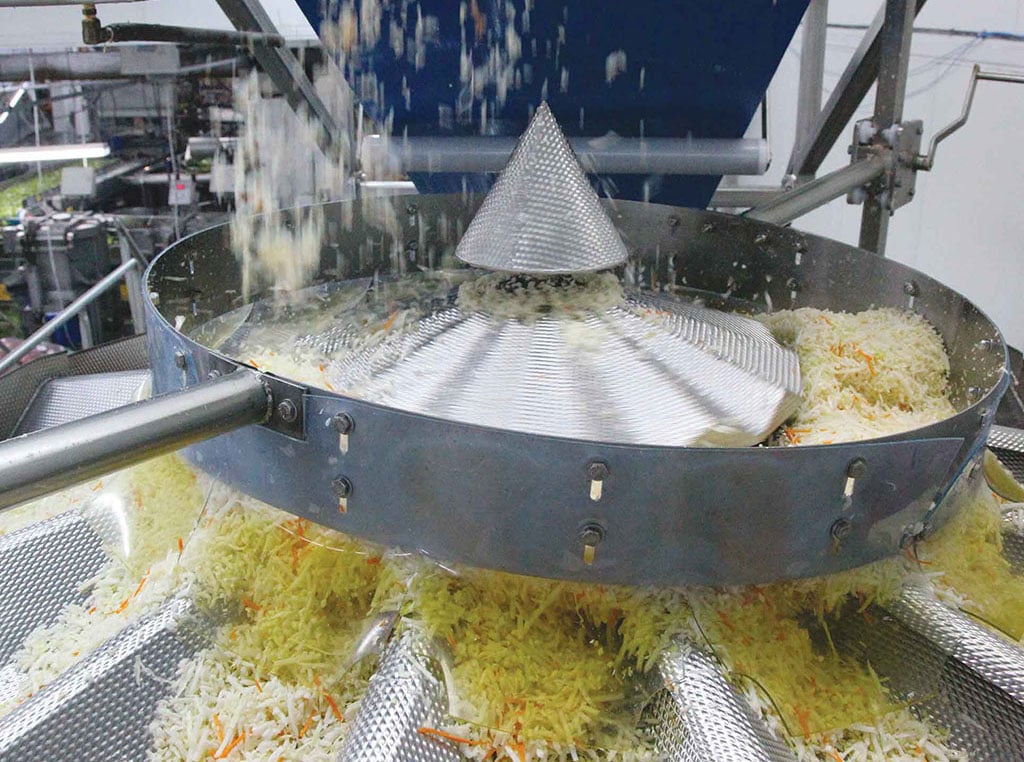

In 2015, Brasso Seco’s families began selling cocoa again—this time, not by hauling raw beans an hour down the potholed road to government buyers in the city, but as their own, premium-quality chocolate. Six farms, each smaller than five acres, provide the beans from their plots in the forest. Fitzjames and her husband Carl wrap the beans in banana leaves and ferment them in a cedar box on their porch for six to 10 days. Then they spread the fermented beans out on a broad table to dry gently for another two weeks.

In a rented room at the village’s community center, Mickell Hernandez makes chocolate in 5.5-pound batches, using machines the size of crock pots. Operating at a tiny scale is a challenge many Caribbean chocolatiers grapple with—European machinery isn’t just too expensive, it’s too big.

Dilean Richards crafts liqueurs with local fruits, flowers, and spices.

At the University of the West Indies near Trinidad’s capital, Renique Murray leads a team of faculty and students that has created prototypes of a suite of 15 “regionally relevant” cocoa processing machines. The group took cocoa processing back to the drawing board to create equipment that is scaled to five-to-10-kg (11-to-22-lb) batches, energy-efficient, easy to maintain with locally available parts, and affordable. Electronic controls give chocolatiers flexibility, while waste heat from one machine helps make the next step more efficient.

“What we’re dealing with here is something that has the capacity to actually adjust the economy of Trinidad and the wider Caribbean countries,” notes Murray, a Ph.D development engineer. “The rising tide floats all boats. If you enhance an industry, you enhance an economy.”

Brasso Seco chocolate bars are marketed through the Alliance of Rural Communities of Trinidad and Tobago, a non-profit founded by local women who taught themselves the chocolate-making business and trained others to do it, too. ARC sells chocolate and other farm products from farms through groceries and gourmet stores, online, and even through Washington, DC, chocolate retailer Soul and Story.

“Chocolate is sexy and exciting,” notes Fitzjames, with her eye on the bigger picture of rural revitalization. “It’s not a jam or juice. It was a great entry point.

“We want to see that all these rural spaces are hubs of creativity and opportunity,” she adds. We want to see thriving rural communities.”

Salad basket. At the south end of the island, where the highway ends, Dominic Sylvan is taking control as he battles the floodwaters that back up in the area’s narrow drainage ditches. Sylvan has invested in 15 stacks of hydroponic vegetable pots, each filled with cocoa peat and pearlite rather than the heavy clay soils his wife’s family has struggled with for decades.

Kelly Fitzjames dries cocoa.

Yards away, his mother-in-law’s three-acre field yields more crop, but Sylvan can tend and harvest his stacks without waiting for floods to recede—something he and other Trinidadian farmers worry will be more of a problem as the rainy season continues its trend toward getting later and wetter.

Sylvan is partial to fast-turnover vegetables like lettuce, green onions, and bok choy, which he can bring to market just four or five weeks after planting.

“I begin at a minute level because of time constraint,” he says. “But I would like to make this my full-time job, doing this at a larger scale—like three times the size of this—to sell healthy food in the market and support my family.”

Between the houses. Many fields in southern Trinidad are more likely to sprout houses than crops. But look between the villa-style homes and the construction sites and you may see Korrie John and his crew farming on the plots that will someday be home to family friends. Before foundations are laid, John farms the properties, squeezing in an acre of peppers here and an acre of cabbage or eggplant there.

After earning his agriculture degree, John worked for the agriculture ministry as a youth agriculture coordinator and for a farm supply dealership as a farm advisor. Over the past six years, he has put his training to work, and is now farming full-time. He irrigates with drip tape and suppresses weeds with mulch. Lined up beside his backpack sprayer, there are far more plant hormones and humates than pesticides.

Daryl Knutt built locked pens for his goats and a block house for himself to deter thieves.

John and his brother Kareem, a BP geologist who has been investing in the land and equipment, currently own five acres, which makes them a large operation in local terms. They are in the process of purchasing 35 more acres to the southwest, where they can focus on longer-term crops like ginger, cassava, and coconut.

John also serves as treasurer of a local farmers’ co-op, formed to educate growers, economize on inputs, and make up for the lack of government farm programs.

“Farmers try to do everything themselves,” John says. “Nobody is there to push the sector. You do what you have to do—it’s just basic, basic, basic. Farmers need to address this together.”

One of the most pressing challenges is access to land. John says fraud is common in land sales. Leases are just as challenging—farmers can wait decades for their applications to be approved. The International Development Bank estimates that as many as 200,000 Trinidad and Tobago families are squatting without lease or title.

During the 10 years that Daryl Knutt has been clearing bullgrass, constructing bee hives, building his goat and beef herds, and developing dairy products for value-added income, he also sought an agricultural lease from the state oil and gas company. Now the company is defunct and so is the government agency that managed state oil lands, stalling Knutt’s efforts to establish himself.

“I would have needed this land tenantship to access loans,” he says.

Knutt is hoping Trinidad’s farmers can push for better land use policies, as well as strengthen the island nation’s ability to feed itself.

You could say he’s hell-bent.

“I felt a need to contribute to food production, toward food security,” Knutt says. “This is my little part. I take it very seriously.”

Read More

Agriculture

Browsing For Options

Goats clear the path for better forage, soils and ranching opportunities.

Specialty/Niche

Supplier of Choice

Commitment to quality pays dividends when the world’s upended.