Agriculture, Ag Tech February 01, 2026

AI in Ag

How artificial intelligence can help farmers become more efficient.

Story and Photos by Bill Spiegel

Spreadsheets are second nature to Adam Baldwin. He uses them to build all kinds of customized formulas for the farm he operates with his parents Dwight and Cindy and his wife Kim.

Last fall, the McPherson County, Kansas, farmer wondered: could he use two trucks at harvest rather than three, reducing the need for an additional driver? His data included proof of yields, truck tare weights and various yield scenarios—the kind of complex and customized equation Baldwin relished. Except during the crunch of fall harvest, he realized it would take time and require a lot of work. Instead of creating a spreadsheet for the purpose, he posed the question to ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence (AI) assistant app on his smartphone.

"ChatGPT," Baldwin notes, "probably took a minute to solve."

To Baldwin, that calculation represented a turning point: ChatGPT, Claude, DeepSeek or any of dozens of AI assistants can help farmers answer complex problems, diagnose repairs, or calculate formulas in seconds.

Quicker and easier. AI's power lies within its ability to simplify tasks, says Jeremy Hewitt, vice president of business development for Tractor Zoom.

"AI will allow us to take care of some of the administrative burden we have in our everyday lives. That will give us more time to spend with families and more time to do things at work that we enjoy, versus being bogged down with day to day operations," Hewitt explains.

Taranis, for example, is an ag-tech firm that uses AI-powered drones to scout farm fields, capturing high-resolution "leaf level" images to discover weeds, insects, and plant diseases, and even perform plant stand counts. Drones fly about 90 feet in the air, and can cover 100 acres in about 35 minutes, says Sarah Rang, the company's director of marketing and communications.

Powerful software coupled with AI algorithms accurately and quickly find problems; agronomists can then follow up by ground-truthing these problems, she says.

Meanwhile, Headcount, a Kansas firm, uses high-resolution drone imagery and powerful algorithms to count feedlot cattle in a fraction of the time it would take pen riders, says Tyson Johnston, director of operations.

"With our system, users select the pens they want to fly, and the algorithm designs a flight plan directly to their drone controller. They set the drone outside, press play and within 15 minutes they have the drone back and within 30 minutes, the count is complete," Johnston explains. It typically takes three pen riders at least five hours.

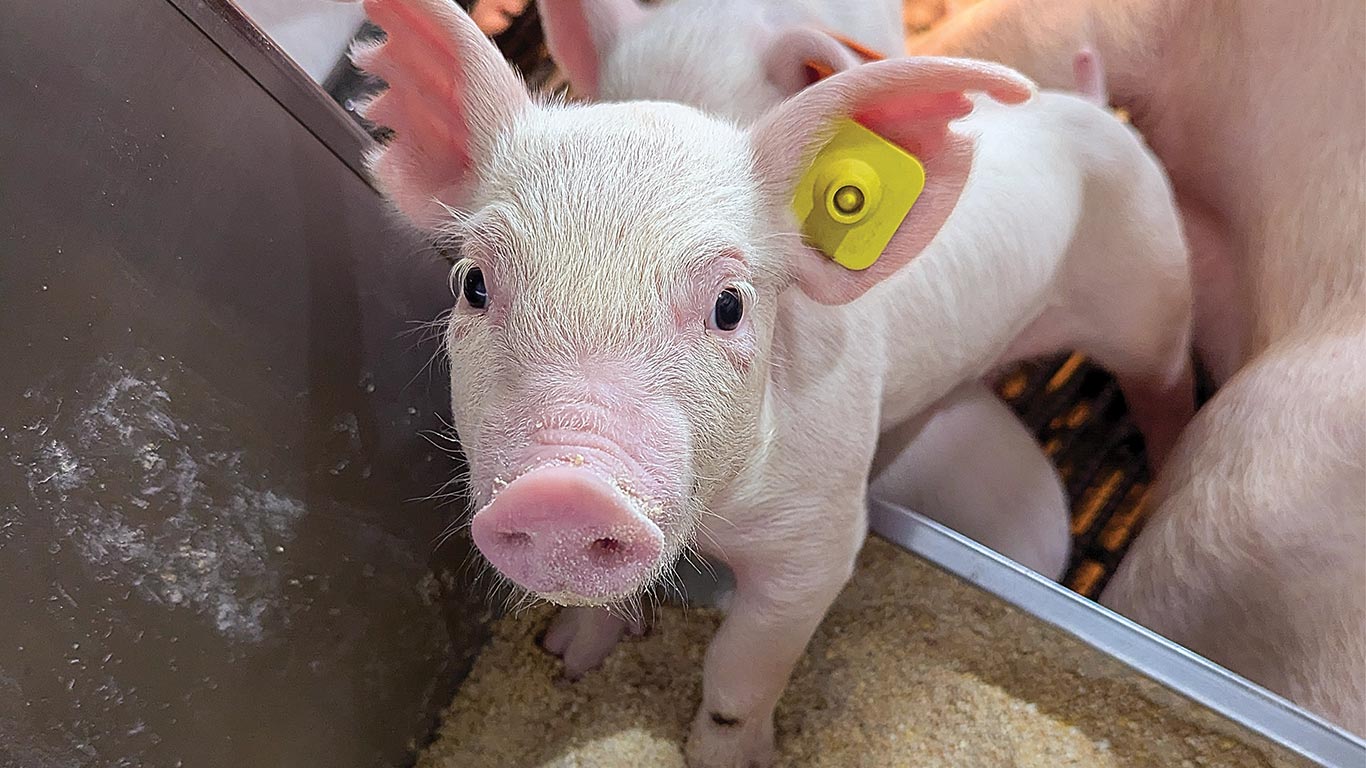

Above. Adam Baldwin says ChatGPT makes complex equations simple. Algorithms and cell or web service helps AI track cattle. Lucas Koch, Kelly Hills Unmanned Systems, tests unmanned aerial vehicles, which use AI in flight plans and agronomic solutions. Drones powered by AI are used by the firm Headcount to count animals in feedlot pens, says chief technology officer Tyson Johnston. Note the tags placed on each animal. Headcount also uses AI to measure feed pile sizes.

"With human to animal contact, at least one animal in a 12-month period will be injured," he continues. "With fat cattle selling for $4,000 per head or more, you've paid for our service immediately."

AI-powered tools can provide real-time feedback on challenges farmers face in the field or feedlot, arguably giving users more bang for their equipment dollar, says Lucas Koch, chief technology officer of Kelly Hills Unmanned Systems, a research and development firm that studies unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones, for agronomic use in real-world situations near Seneca, Kansas.

These are machines potentially worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, equipped with sensors, cameras, hardware and powerful software that enable grounded pilots to perform precise agronomic functions with fewer people who require specialized training, Koch says.

Farms and ranches are adopting AI at a rapid rate. The ag tech company Farmonaut projects that 45-50% of large-scale farms throughout the world are using AI-driven technologies, including AI assistants, precision satellite imagery, drone surveillance, or "internet of things" sensors to acquire real-time data.

The pitfalls of AI. AI is not without drawbacks, however.

There are certain trust limitations with AI, as algorithms "learn" based on information that is fed to them, which may or may not be accurate, says Bart Peintner, CEO of Elemental Agronomy Robotics.

"I use AI on a daily basis. I trust it after it proves itself to me," Peintner says. "The valid viewpoint of, should I trust AI or not is not a binary answer. It's like having a new employee in that you trust them after you see they're doing the job."

The more AI is used in agriculture, whether smartphone apps or on-the-fly data gathering, the more useful it becomes. And to Baldwin, the future is exciting.

"More processes will be turned over to decision bots, and small autonomous systems will take off," he says. "AI is the future. We'll end up using it in ways we can expect, and in ways we never could have imagined." ‡

More articles related to:

Read More of The Furrow

AGRICULTURE, AG TECH

Intelligent Solutions

Artificial Intelligence—and human intelligence—point the way to better crops and crop protection.

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Livestock Innovation Robotics and Data

01100100 01100001 01110100 01100001