Agriculture, Ag Tech February 01, 2026

A Future in Gene Editing

Amending the DNA of success.

Story and Photos by Martha Mintz

Ctrl X. Gene editing isn't quite the breeding equivalent of this useful keystroke combination, but it's quick, accurate, and the results are coming to a barn near you sooner than you might think.

Selective breeding to propagate desired traits has long been a slow and inexact, yet useful, process. Gene editing technology essentially cuts through the guesswork to deliver fast, accurate, targeted advancements.

"Gene editing is a tool we can now use to go into the genome and write very specific changes in the DNA to give animals the traits we want," says Elizabeth Maga, professor of applied molecular genetics, University of California, Davis Department of Animal Science.

The traits gene editing stand to improve go well beyond those that traditional selective breeding brought us, like coat color and milking ability. Gene editing is being used to develop traits in goats, sheep, cattle, swine, and poultry that could truly revolutionize livestock production.

Traits for managing tough diseases, overcoming environmental challenges, finding production efficiencies, and improving animal welfare are well in the works.

In 2023, scientists produced the first gene-edited calf resistant to bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV). Others have produced beef and dairy cattle that have slick coats for improved heat tolerance in hot climates. Ongoing research is being conducted for gene edits that result in cattle that only produce male (beef) or female (dairy) offspring.

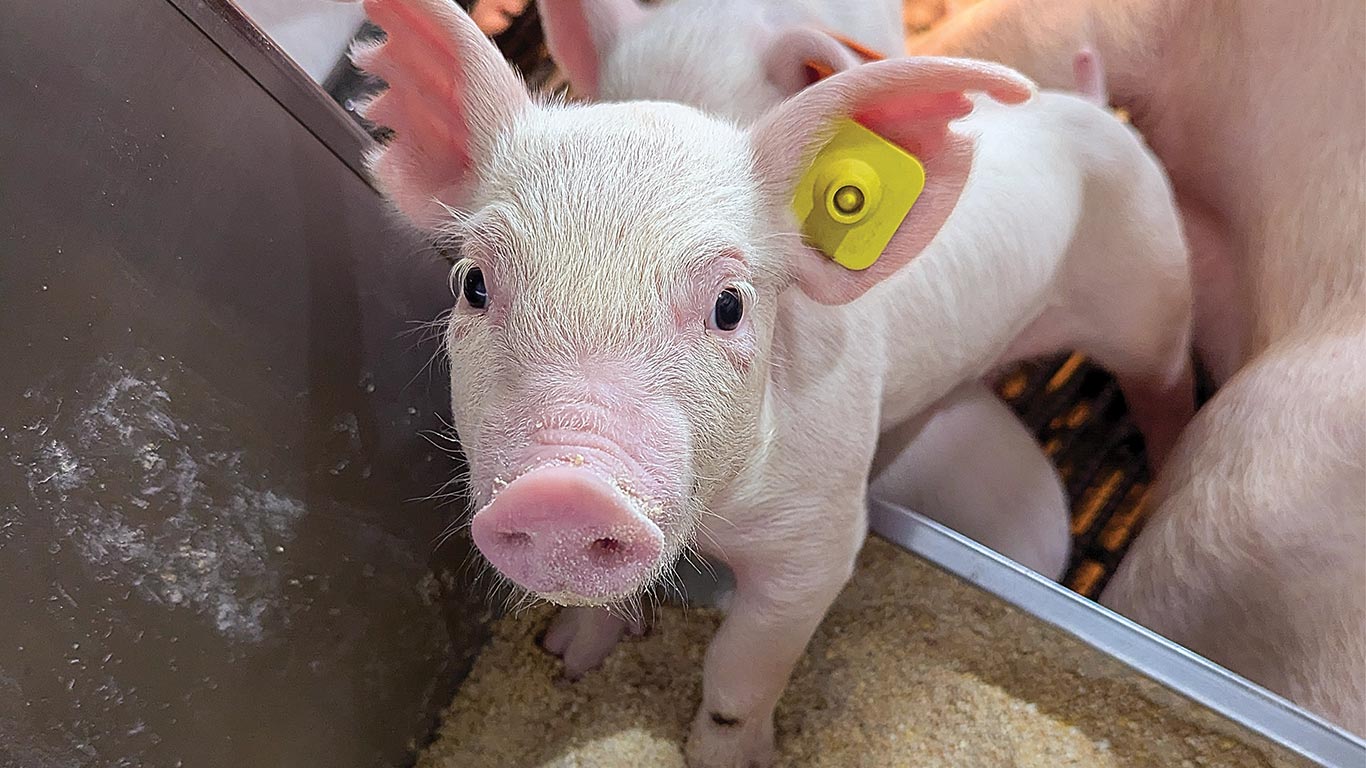

A UC Davis project aims to eliminate boar taint. The theory is gene editing can be used to delay or prevent puberty so boars no longer produce strong odours or need to be castrated—a solution that improves animal welfare.

Less than a year ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted the first regulatory approval for use of gene editing in commercial livestock production to the Pig Improvement Company (PIC). They used gene editing technology to develop pigs resistant to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS).

Above. Over the course of her career, molecular geneticist Elizabeth Maga has seen gene editing advance from an aspirational dream to a functional technology poised to fast-track genetic-based livestock performance advances.

"It's among the world's most common and costly diseases," says Banks Baker, PIC Senior Director of New Product Strategy.

From 2016-2020, the disease cost an estimated $1.2 billion in losses each year—an 80% increase over the previous decade according to an Iowa State University analysis. The increases are in spite of advancements in biosecurity measures and vaccines, he says.

"We believe the genetic solution is the most effective option," Baker says. The company is holding commercial release for approvals in key international markets.

With the first FDA approval stamped, Baker hopes the path PIC has helped blaze will make the approval process more streamlined for the next applicant.

Meanwhile the processes of gene editing are being continually honed by scientists like Maga.

"We're working to optimize these technologies in livestock embryos and stem cells," Maga says. Better technologies and processes will help streamline the process for future advancements.

Early gene editing was an inefficient and random process. A piece of DNA was injected into a single-cell fertilized egg and then hopefully taken up by the genome in a useful way.

This tactic was used to add a gene for growth hormone production into a mouse in 1982.

Dolly the cloned sheep was created as part of a strategy to improve efficiency. The real breakthrough, though, came in 2012 with the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Now, guide RNA escorts an enzyme to a specific target on the DNA strand. The target is knocked out and a desired result attained. Maga's lab is researching how well edits hold up over time and ways to detect edits.

"Gene editing was sort of the dream when people started working in the field of transgenics decades ago. That dream has come true," Maga says. What's next?

"Can we get even more specific? Can we do a one-stop shop and change many things at one time? I don't know. The sky's the limit at the moment." ‡

More articles related to:

Read More of The Furrow

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Livestock Innovation Robotics and Data

01100100 01100001 01110100 01100001

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Changing Landscapes

Economic pressures have created a new rural landscape in Canada.