A Kansas wheat farmer shares highlights of a lifetime gathering farm magazine photos and stories.

Agriculture January 01, 2021

An Agricultural Odyssey

Reflections on 46 years of covering innovations in agriculture.

When The Furrow’s editorial staff decided to use a series of personal essays in this issue to reflect on the magazine’s 125th anniversary, it was sobering for me to realize that I’ve been writing about agriculture for a significant portion of the magazine’s history—46 years to be exact. So, what better way to reflect on the legacy of The Furrow than to look back at the dynamic changes I’ve witnessed—and people I’ve met—in my odyssey through agriculture. The bulk of my writing career has been with Successful Farming (14 years), Farm Journal (12 years), and The Furrow (18 years). I’ve also operated our family farm in Kansas since 1988—that’s me going ‘round and round’ the wheat field above. In similar fashion, I’ve gone ‘round and round’ the seasonal rituals of production agriculture since 1975. Stories on those farming practices required photography and that meant finding and visiting innovative farmers and researchers on the leading—and often bleeding—edge of crop production and farm management.

In rough numbers, this effort has taken me to perhaps 5,000 farms, field days, conferences and meetings across the country and around the world. Only once have I not been warmly received, so I’ll take a few lines to tell that story.

Early in my career I was in southern Minnesota scouting for grain handling stories. I’d learned of a unique system built around a pivoting auger. My repeated calls were answered by a young girl saying ‘daddy’s not home.’ Nearing the end of my trip, I asked her to ‘tell daddy that a man from a magazine wants to look at his grain bins.’

He didn’t get the message. The next morning I pulled in the yard to find the farmer at the shop fixing the outrigger on a disc. His son, whom I later learned hit a telephone pole with the disc, was across the yard throwing dead hogs out of a pen. My overture was quickly met with the response ‘the last damn thing I need now is a magazine editor.’

I promptly left, but in full disclosure the son caught me two miles down the road and apologized. My hat’s off to the thousands of others who’ve welcomed my intrusion and been anxious to share their ideas, opinions and innovations.

Whirlwind of change. Much has changed since my first byline appeared in Successful Farming in 1977. That article debated whether or not farmers should continue using the moldboard plow and espoused the benefits of a residue-free seedbed that dried faster and warmed more quickly. Two years later, I couldn’t convince my editor to run a story on Lovington, Illinois, farmer Byron Boody, who was planting corn in a cover crop of 4-foot tall rye. ‘Surely he mows and bales the rye before planting,’ I was told.

Fast forward four decades and 104 million acres on 280,000 farms in the U.S. now use no-till practices. In the last decade, the soil health benefits of cover cropping has been added to no-till with leadership of farmers like North Dakota’s Gabe Brown. According to the most recent census, 153,400 farmers are now planting cover crops, including Kansas farmer Josh Lloyd, who was featured in a recent The Furrow article while ‘planting green’ in standing rye. Other noteworthy topics in my string book from the late 1970s include a study from Iowa State on depth control on planters ‘equipped with runners’—rather than today’s single or double-disc openers; how farmers could financially survive in an ‘era of $40,000 tractors’—comparable to $150,000 for a similar model today; and seemingly endless stories on how farmers built their own narrow-row soybean planters.

In 1980, Gothenburg, Nebraska, farmer Floyd Wahlgren shared with me his strategy to push the capacity of his 8-row planter to 160 acres per day. According to posts on a popular online farm forum, today’s farmers running high speed, 24-row, central-fill planters with auto-steer cover nearly 500 acres. Of course, planters aren’t the only thing that’s gotten bigger in my tenure as a farm writer. Throughout the 1970s and 80s the push was on for bigger sprayers, larger nurse trailers, wider fertilizer bars and tillage tools and fancier shops to care for it all. Farmers like Jerry Brechon in Dixon, Illinois, and Dwayne Blankenship in Wastuchna, Washington, seemed to revel in the challenge of building equipment bigger than anything commercially available. Their ideas and ingenuity made great stories.

In 1978 I encountered a classic example of farmers building what they couldn’t buy on the Keller farm near Blairsburg, Iowa. That’s when Gene, and his father Joe, rolled out a model 4440 John Deere tractor that they had transformed into a highboy sprayer. The unit cleared tasseled corn, straddled four rows and sported a boom that spanned 108 feet. The one-of-a-kind unit foretold of the self-propelled highboy sprayers that are now common on today’s farms. As an aside, the Kellers planted corn in 40-inch rows and I was naive enough to ask Joe why he didn’t change to the more modern 30-inch rows. ‘When I want more rows of corn I’ll buy more land,’ he confidently replied.

Precision revolution. For much of my career I’ve followed the development of precision agriculture. Now a giant in that realm, Ted Macy was more a wild-eyed dreamer in 1990 when we lined equipment up in his Cambridge City, Indiana, field to illustrate site specific, variable-rate farming. Combine yield monitors are now used on 80% of farms, but the idea was merely a series of augers and conveyors spilling grain on the shop floor when I visited the J.P. Faivre farm near Dekalb, Illinois in 1990. Partners Steve Faivre and David Larson ultimately patented their version of the revolutionary idea of measuring grain volume through the combine to create yield maps. A series of stories themed Farming by the Foot obviously underestimated the technology’s ultimate centimeter-like accuracy.

The average wheat yield in Kentucky was 33 bushels per acre before crop consultants Chris Bowley and Phil Needham arrived from England armed with intensive management ideas from Europe’s 150-bushel per acre sphere. Bouncing over the hills of Western Kentucky, Bowley took me to visit Joe Wayne Hendricks and other farmers who would adopt the practices that have since raised the state average yield to a record 80 bushels per acre in 2016. Meanwhile, Needham has gone on to promote improved wheat management practices throughout the U.S.</p˘

There are scores of others to mention, like Dwayne Beck, whose message of no-till and crop diversity has transformed agriculture in South Dakota and beyond. And credit to the host of university researchers whose facts and figures have supported so many of the stories I’ve written. The low point of my 46 years? There’s the DEA agents who were convinced I was photographing NH3 tanks in Central City, Nebraska, as part of a meth operation. Sadly, they’d never heard of The Furrow and hinted that a cavity search was one way to prove my innocence.

Read More

Agriculture

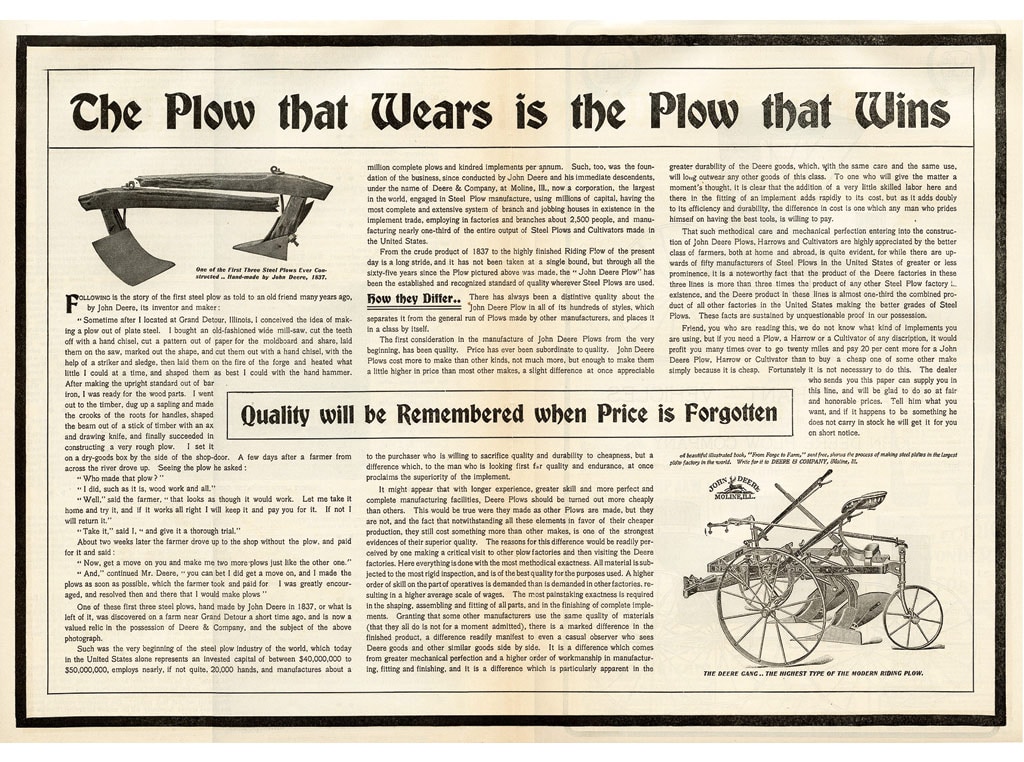

Plowing A Straight Furrow

For 125 years, The Furrow has been documenting the ebb and flow of farm life.

Agriculture

Faces of The Furrow

For 125 years, The Furrow has told the story of agriculture, and the stories of agriculture.